Creative Licensing and the Art of The (bad) Deal

Changes needed for a fairer future

Contents

- Earning a Fair Wage

- Skewed by the Long Tail

- Gate-Keepers and Rent-Seekers

- Lower Costs, Higher Prices

- Could Licensing Companies Do More?

- Blockchain, NFTs and Validity

- The Future

Earning a Fair Wage

A universal truth is that everyone should be paid fairly for their own labor. When you are directly paid to build a wall or assemble widgets it’s easier to determine what may and may not constitute “fair”. It becomes more complicated with creative endeavours.

Something that many don’t understand about economics is that pricing often includes the time spent not directy “doing the work”. We may balk at the call-out fee for a plumber in the early hours, but factored into that is the time spent waiting for a call to happen and being ready to respond. Sure, the fix itself may only take 30 minutes … but if they were only paid for the time actually spent holding a wrench then there would be no plumbers available.

Likewise, with work that involves some accreditation and accumulated know-how such as a lawyer or a doctor. You are not just paying for the time you consult with them, you also pay for the years of study and training that enable it to happen and that makes them qualified.

When it comes to creative works, many just see the final product and imagine it was quick to produce, and don’t appreciate all the time practicing, discarding failed projects, honing things to perfection and the time and materials consumed while learning.

If you watched the recent Beatles “Get Back” documentary or listen to Bob Dylan bootleg series of studio out-take recording, you realize that the version of the song you heard all those years ago was the end result of many hours or even weeks of work, and songs often evolve though many versions.

There is a somewhat mythical image of the “starving artist” which isn’t fair if true - why shouldn’t a writer, composer, singer or painter be able to earn an equitable living wage for the work they do? We shouldn’t expect them to create things for nothing, but how should they be compensated for what they create?

Skewed by the Long Tail

Our view of artists is very skewed because there is a real “long tail” effect when it comes to success. This means that the small-handful of the most successful artists often account for the vast majority of the market with things quickly tapering off toward lots of people earning very little.

Of course the artists we know and see promoted are usually those that are economically successful and what we make the mistake of viewing as “the norm”, instead of the exceptions or outliers. Althought there are millions of books, paintings and songs available to choose from, the vast majority of people all read, view and listen to the same narrow selection - those at the top. It’s a “winner takes all” effect.

The sight of multi-millionaire artists living lavish lifestyles can make us imagine that the life of all creative types is an easy one - just create something and then live off it for the rest of your life! Why doesn’t everyone just do that?

Well success is only partly about talent.

Gate-Keepers and Rent-Seekers

The world of instant digital publishing and sharing that we live in today wasn’t the same in previous decades. Back then, however good you were, you couldn’t get featured on the radio or hung in a prominent gallery without the approval of someone else. And that approval came at a cost.

These gate-keepers had to the power to pick and choose which talent could actually have a shot at becoming a commercial success and offer them contract terms that were extremely beneficial to the gate-keepers, but less so to the artist.

Sure, there are always feel-good stories of artists breaking through based on their raw-talent alone, but the reality was often that even they got screwed over by the distribution companies that controlled their industry and artists such as the Beatles and Bowie really had a decade of hard-slog behind them before they were “an overnight success”.

Once successful beyond a certain point, the biggest artists are able to renegotiate contracts to receive a better deal, but this is atypical to the market as a whole and they still had to deal with the “rent-seekers”.

Rent-seeking is an attempt to obtain economic rent (i.e., the portion of income paid to a factor of production in excess of what is needed to keep it employed in its current use) by manipulating the social environment in which economic activities occur, rather than by creating new wealth. Rent-seeking implies extraction of uncompensated value from others without making any contribution to productivity.

Basically, companies set themselves up as middlemen, only allowing the work of others to be rewarded if they pay them their fee. These middlemen don’t really add value, they don’t create, they don’t even do much to protect the artists interest - but they always take their cut.

Lower Costs, Higher Prices

Again, the world of today is not the world of past decades. At one time a vinyl record had to be pressed, album sleeves printed, records shipped to stores and so on. The same with books - think of all the processes that go into making paper, typesetting, printing and assembling books and the cost to ship the heavy boxes to physical stores. Now both are just a few megabytes on a server and thanks to technology innovations that digital storage is incredibly cheap.

When you see the multi-billion dollar tech companies making money from music streaming you may be surprised to hear they they only pay fractions of a cent to an artist for the streaming of a song. Music artists only receive 1/10th of the revenue that the music industry generates. The rest goes to the companies that distribute and promote it, even though those distribution costs are now a tiny fraction of what they once were.

Why then are customers still charged comparatively high prices? Partly because it’s what the market will bear - if people were used to paying $19 for a physical album, they will pay $0.99c for a digital song and the convenience. Again, with books - occasionally the Kindle version is much cheaper, but most often it seems to be a case of “if people will pay $39 for a physical book, they’ll pay $35 for the digital one”, even though you loose the ability to pass it on to friends or family like you can with a real hard copy.

So we now have distributors still charging the same or even more but doing much less with lower costs. Customers still pay high retail prices as a result and despite that, little of the revenue actually goes to the creators.

It’s not a tolerable system, let alone an ideal one. Surely something has to give?

Could Licensing Companies Do More?

Of course some would argue that licensing companies do provide a value-add service. Technically, yes, they do. But are they really doing all that they could and enough of what they should?

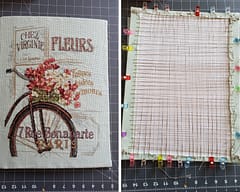

Let’s focus more on the specifics of art-licensing and how it relates to cross-stitching.

Here are the typical economics of cross-stitching as it relates to imaeg-to-pattern conversions of artwork:

Take a pattern selling for $20-$30 in digital form. Despite what some claim these really only take a few minutes to “create”, sometimes seconds. The storage and distribuition costs are practically zero, certainly negligable.

The cost for licensing the artwork can be 10-15% of the price, approximately $2-$4, and it’s not unusual for the art-licensing company to only pay 50% of that to the artist. So from the $20-$30 sale only $1-$2 may be going to the artist. The rest is profit for the store and distributors, the middle-men.

Why are patterns $20-$30? Because it’s what the market will bear. Remember the Kindle example? That happened with cross-stitching too. At one time, you may have bought a kit for $30-$40 and at some point people wanted to just buy the patterns and selling them digitally over the internet made sense. $20-$30 is what the market will bear and what people were charged, even though creating a pattern really only takes minutes and the same pattern can then be sold over-and-over. The major part of the price of a kit wasn’t the pattern, it was the materials.

Notionally, art licensing companies, protect against copyright violations, but do they really? Big companies such as Disney may be litigious and actively pursue violations (when they are not ripping people off themselves!) but they typically focus on large commercial manufacturers of unlicensed products.

Do the licensing companies actively promote the artwork they represent? No, they don’t call people or send mailshots to potential buyers, they rely on the buyer coming to them. Many don’t even return emails when you make an enquiry about licensing the art or even have functioning websites - heaven knows what revenue the artists who use them receive, if anything.

The only thing a licensing company really provides is a single point-of-contact for the artist. Rather than negotiating with individual licensees, the artist only deals with them, but in doing so they give up control and immediately lose whatever amount the licensing company is going to keep (50% or more is not unusual).

Blockchain, NFTs and Validity

Let’s start by acknowledging that completely preventing piracy of digital assets is for all intents and purposes impossble. It’s so easy to make a copy and share a digital file. The only counter to it is legal prosecution, which even the likes of the powerful music and movie industry struggle with, and with education.

But people often forget that in between the legitimate buyers of licensed products, and the hard-core pirates, are those who inadventently purchase some unlicensed product because they don’t know and can’t tell what is and isn’t genuine.

This is one area where art licensing companies badly let down artists. Can you, for instance, go to their sites and check if a product you are thinking of buying is licensed or not? No, you can’t. Isn’t that odd?

Now imagine if there was a way for someone to check if the product they were buying was approved by the artist who’s work it was based on?

One solution to checking the validity of a pattern would be blockchain and NFTs. You may have heard of the blockchain in relation to cryto currencies such as Bitcoin, but all you need to know about it is that it’s an immutable public ledger - that means it’s a trail of transactions that anyone can read but no one can modify, and each transaction validates who made it (nothing can be forged).

A recent development is the sale of NFTs or “non-fungible tokens”. These are effectively unique pieces of digital art which, unlike a regular digital image file, can be absolutely proven to be owned by a specific entity. They can be bought and sold like any other asset, and the transfer is recorded on a blockchain.

Not only can you see who currently owns an NFT, but you can see who has ever owned it, all the way back to the original creator. Also, unlike traditional art sales where the artist receives nothing extra for any subsequent transactions, an NFT can enable an artist to receive a percentage of any re-sale - so they can benefit from any appreciation in the price of their work over time.

We believe the future of art-licensing and sales of digital products based on licensed artwork will involved the blockchain and NFTs as a means of both recompensing artists and verifying that the product was approved by them. A browser extension could immediately tell if something was legitimate or not to make it easier for users to do the right thing with fare less effort.

The Future

But technology is only part of the solution. The other factor is pricing. Why do people create unlicensed products? Because there is economic incentive - potential for huge profits! We’ve already seen than the “licensing” part of the price is very low and these high profit margins are an incentive for people to sell unlicensed products to unwitting buyers.

A recent trend in the music industry is self-publishing. Rather than going through the incumbent distribution chanels, people can now reach an audience directly over the internet. Writers and artists can do the same. They can sell their works at a lower price but make more money at the same time, because more of it comes to them.

We’ve long touted a model for the cross-stitching industry be one where artists could license their images to a pattern vendor or even make and sell cross-stitch patterns directly themselves. All they need is a platform to enable it.

Imagine this …

The current legacy system which hasn’t changed in 20-30 years has customers paying $20-$30 for a pattern with $2-4 going to an art-licensing company, $1-$2 going to the artist (sometimes 6 months to a year later) and the remainging $18-$26 being kept by the seller. This incentivises unlicesed sellers who can easily sell patterns for $10-$20. Even worse, the exact same digital file is given to each buyer which makes them easy to re-sell or share, contributing to the piracy problem.

What if, instead, someone developed a platform that used modern technology to improve efficiency and lower costs?

What if they only charged customers $10 for a pattern, but paid 50% of that straight to the artist? Or what if the platform allowed the artist to create their own store, easily chart their own patterns, and keep 80% of the revenue themselves from each sale?

What if PDF patterns were embeded with the buyers details to disuade people from copying and distributing them?

What if PDF files were not even required, and people could instead us a free app to view and track their patterns as they stitched?

We believe the future of cross-stitch is digital with artists taking control of their work to get the cut they deserve.